What started as a simple food recommendation spiralled into something deeper. A comment, a reaction, and the questions that followed. This is a reflection on ego, exhaustion, and who gets to decide what counts as local.

It started with a pizza. Or rather, a question wrapped in judgement: “Going to the Philippines and eating a pizza, seriously?”

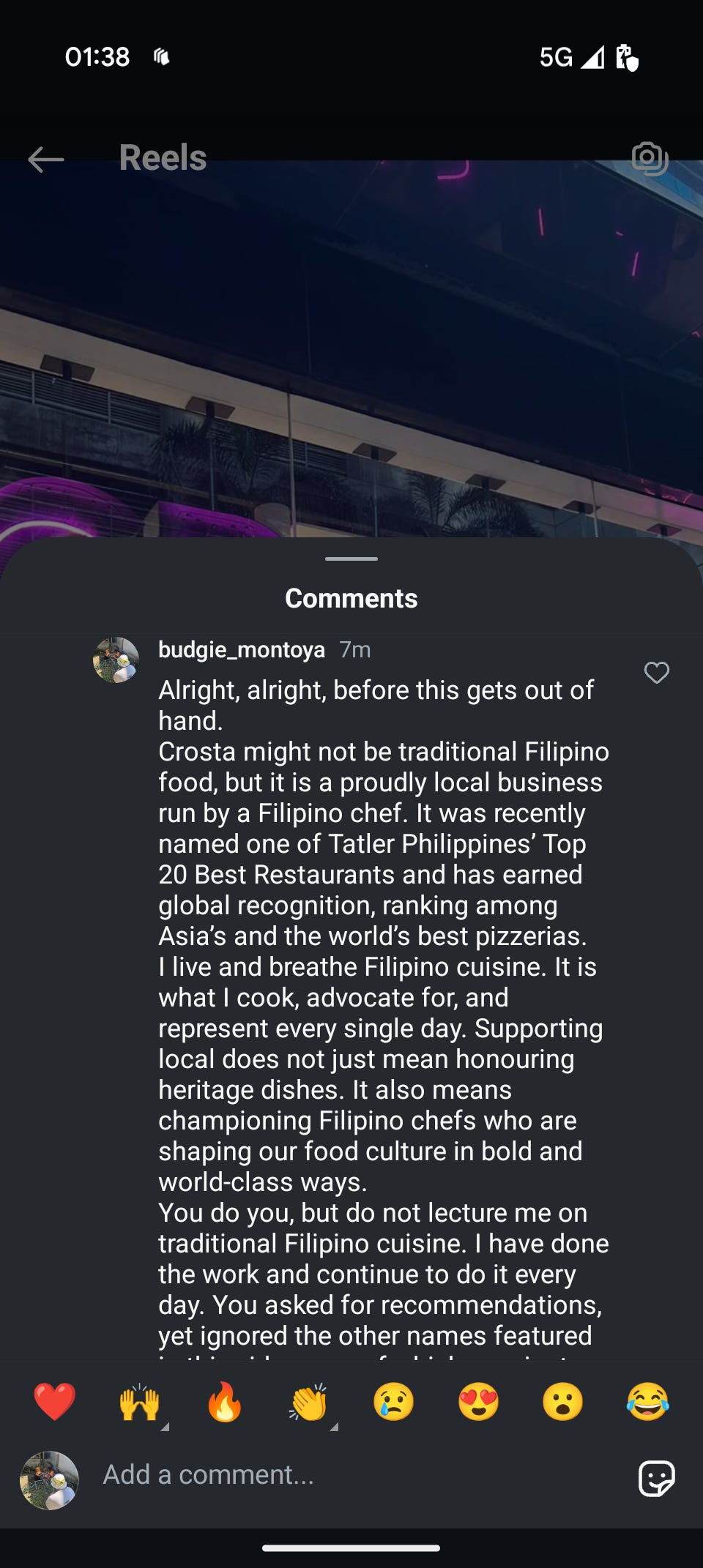

The comment sat under an old reel I filmed for a marketing agency I’ve worked with for a number of years, It was posted way back in July last year. They had asked me to share some standout spots from a trip to Manila, and I offered a few personal favourites. One of them was Crosta, a proudly Filipino-owned pizzeria that has earned local and international recognition. Recently named one of Tatler Philippines’ Top 20 Restaurants and consistently ranked among Asia’s best pizzerias, it represents the creativity and ambition of Manila’s dining scene today.

When I travelled to Manila on this occasion, it was the first time in well over thirty years. Even then, my childhood memories of the city were mostly brief stopovers on the way to Davao. This was the first time I had the chance to experience the capital with intention. I had never heard of Crosta before. It wasn’t something I sought out to prove a point. In fact, it was the locals who recommended it, everyone from the kuya working security at my hotel, to chefs, bartenders, waiters and even family based in Manila. They all told me to go. And I’m so glad I did.

But that detail did not seem to matter.

The follow-up comments came quickly. “If I want a pizza, I go to Italy. If I want a croissant, I go to France.” She went on to call the choice a waste of time and money. “There are better things to eat in the Philippines,” she insisted. “Not something I can eat everywhere in Europe.”

I should have let it go. But I didn’t. I replied. Frustrated. Blunt. A little sharp. And if I’m honest, a little wounded too.

At face value, her comments might seem like nothing more than a strong opinion. But they were layered with the kind of casual superiority that so often hides behind “honest feedback.” Her words may not have been intentionally harmful, but they echoed an all-too-familiar tune: the idea that Filipino food must fit a narrow, traditional mould to be seen as valuable. That our chefs cannot possibly reimagine or recontextualise global dishes on their own terms. That our cities cannot produce world-class cooking outside the lens of European comparison.

This is not about pizza.

This is about who gets to define what is worth eating in a place like the Philippines. This is about what happens when a European traveller feels entitled to lecture a Filipino chef about his own country’s food choices. This is about the quiet violence of cultural gatekeeping, dressed up as culinary standards.

Crosta is not a gimmick. It is not some watered-down, Westernised concept parachuted into Manila. It is a product of local ingenuity, owned and operated by Filipinos, shaped by their experience, their craft, and their taste. It is precisely the kind of local business that should be celebrated. Just because it serves pizza does not mean it is disconnected from its roots. Local does not always mean ancestral. Sometimes it means present. Sometimes it means what we are choosing to make, right now, with pride.

I was born in the Philippines, but I’ve lived most of my life abroad. Australia shaped my early years, and I’ve built my culinary career in the UK. I’m part of the Filipino diaspora, and I carry the contradictions that come with it. I may not speak Tagalog fluently, and I didn’t grow up with daily access to carinderias, but that does not make me any less Filipino. My love for the food of my heritage is not a performance. It’s a process of return.

I have spent years fighting for Filipino food. I have written about it, cooked it, defended it. Not just in the Philippines, but across the diaspora. I have seen it misunderstood, stereotyped, ignored. So yes, when someone reduces that work to a lazy punchline about pizza, it touches a nerve. I carry that weight with me. We all do, those of us who have had to work twice as hard to prove our cuisine deserves a seat at the global table.

But I also want to be honest with myself. My reaction was not just about justice. It was also about ego. About being tired. About having to explain, again, that Filipino chefs are allowed to be many things at once. That we are allowed to make sourdough, pasta, ice cream, ramen, and yes, pizza. And that we do not lose our cultural identity when we do.

It didn’t help that I had posted a story on instagram in the heat of the moment with a caption that read, “ummm who wants to tell her?” The tone was flippant, reactive. Some friends and a former sous chef chimed in, no doubt encouraged by the post. In some ways, I appreciated the solidarity. In others, I knew I had contributed to escalating the situation. I had opened the door to a pile-on, even unintentionally. And that made me pause.

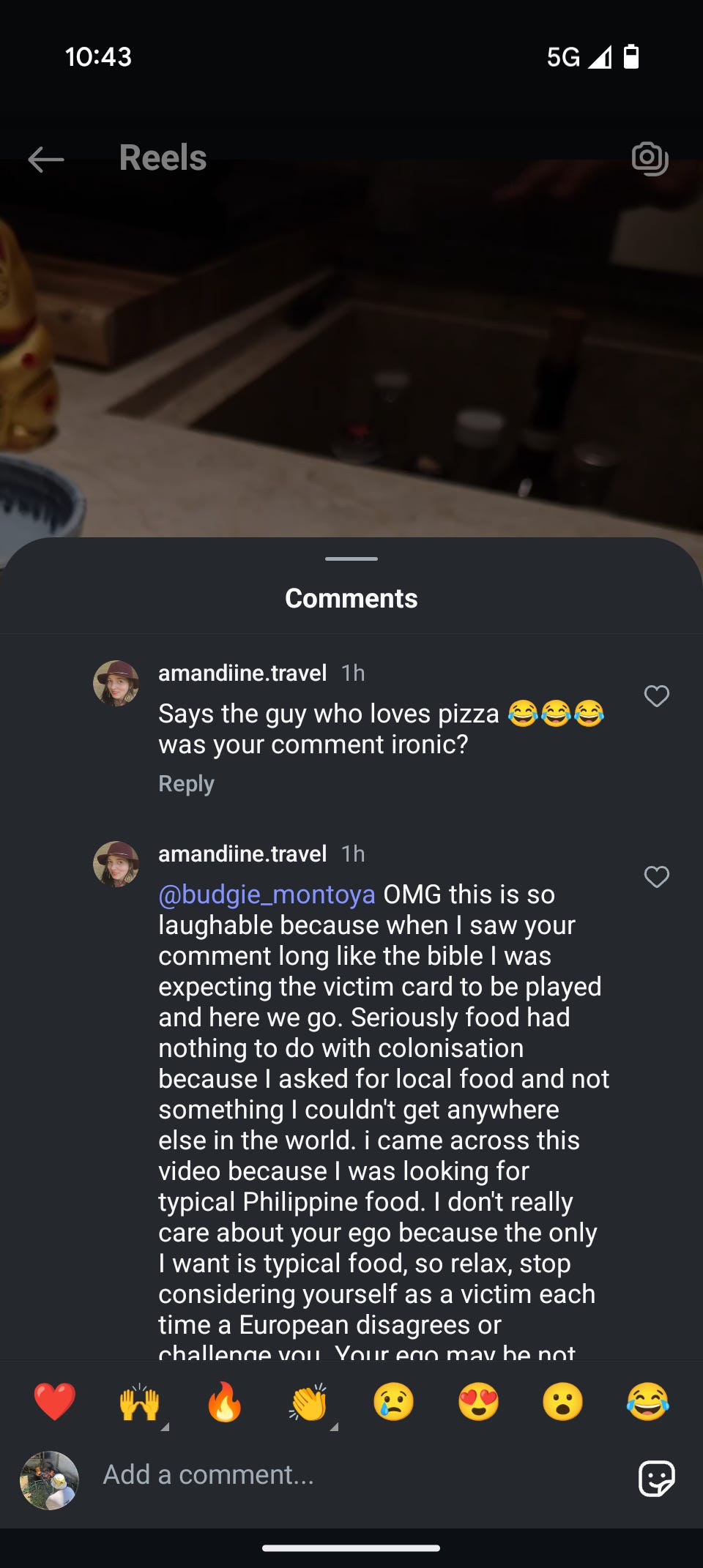

What followed, though, revealed something deeper. Her next comment dismissed my response as “long like the Bible” and accused me of playing “the victim card.” She said food has “nothing to do with colonisation,” that I should stop “considering myself a victim each time a European disagrees or challenges me.” And just like that, a conversation about local food turned into a lecture on how I was meant to feel about it.

This is the part that stings more than any pizza joke. The way a defensive tone becomes a tool of dismissal. The way historical critique gets rebranded as emotional excess. The way nuance is flattened into a tired stereotype: the brown man who talks too much and takes things too seriously. It is a tactic I’ve seen before. You challenge power, and suddenly you are accused of being too sensitive. Too political. Too much.

Her words are a masterclass in how structural privilege hides in plain sight. The denial of colonial legacies in food is not just historically wrong, it is a refusal to see how power shapes palate. Cuisine does not evolve in a vacuum. It is shaped by trade, trauma, displacement, access, and yes, colonisation. To say “I just wanted something typical” without interrogating what typical even means, or why certain foods are expected while others are deemed inappropriate, is a form of soft violence. It reinforces the idea that Filipino food must serve a specific performance of identity to be respected.

There is a cost to constantly defending the legitimacy of your culture. It wears you down. It makes you reactive. You start to feel like every ignorant comment needs correcting, every insult needs confronting. But not everything deserves your energy. And not every disagreement needs to become a public reckoning. That is something I am still learning.

Still, I do think it matters to talk about these moments. Not to cancel someone. Not to centre the conflict. But to hold up a mirror to the assumptions we all carry. The assumption that tradition is more authentic than innovation. That heritage food must always look like it did fifty years ago. That the global South can only be appreciated through the lens of the past, never the future.

The truth is, local food scenes are more complicated than postcard versions of authenticity. Manila is not a museum. It is a living, breathing city. Its food reflects that. To truly honour a culture is to see it in motion, not just in memory.

So to those who visit places like the Philippines and expect them to perform a fixed idea of themselves, I say this: your taste is not the only taste that matters. And your idea of authenticity might be the very thing holding others back from fully expressing theirs.

And to myself, I say this: you do not have to fight every battle. But when you do, make sure you are not just defending your pride. Make sure you are defending something deeper. Something truer. Something worth building.

Because Filipino food is not just about what we eat. It is about who we are allowed to be.

These kinds of responses often repeat themselves. They insist that food is just food, that history is irrelevant, that asking these questions is playing the victim. But what they reveal, over and over, is not a lack of understanding, but a refusal to listen. This was never about winning a comment section argument. It was about naming a pattern, one that keeps so many of us small, quiet, and apologetic for simply taking pride in who we are and what we make.

This piece is also a reminder to myself. I am not only recovering from heart failure, I am also learning to heal from the quiet damage caused by years of burnout. The kind that creeps in when you carry too much, for too long. The kind that turns every comment into a confrontation, every moment into a test of your worth.

Writing this helped me step back. To recognise the difference between defending culture and defending ego. To remember that not every reaction needs to come from exhaustion. Some can come from clarity, and compassion, especially towards myself.

There is still so much I want to fight for. But I also need to rest. And I need to grow. Both can exist at the same time.

It's a bit like the discussions I have with people who want recommendations on where to travel in the Philippines. So many people say that they're told to avoid Manila as an 'ugly' typical Southeast Asian city - just to head straight to the islands and the beaches. But that's part of the charm of why I like Manila (besides the bias of my mum being from there): it's a massive city that has its own beating heart and its own energy that is not restricted to the 'picture-perfect' idea of what a tropical paradise should be. Yes, it's a messy city, yes it can be intimidating for newcomers and yes it can be very frustrating at times even for those familiar with it, but there is a lot happening there that is both exciting and challenging. And as the economic, political and economic hub of the country, there will of course be a lot that people miss out on by knee-jerkingly skipping the place

When I'm travelling, of course I want to prioritise eating things I can't get at home. But to think that cuisines aren't allowed to adapt and grow because they're "ethnic" or "traditional" is asking cultures to preserve themselves in aspic for your entertainment, and what kind of arsehole wants that?

I love seeing what different countries do with gua bao, because (like pizza!) the options are almost limitless and they're an inexpensive way for chefs to experiment with new flavours and old memories.