Manila to Acapulco: A Route Without Recipes

For years I’ve chased the idea of a culinary bridge between the Philippines and Mexico. But what if the real story isn’t about recipes, but erasure? This essay follows the Manila–Acapulco galleon trade and the fragments it left behind, not on the plate, but in the silences.

Back in the early days of Sarap, around 2017 or 2018, I started experimenting with crossovers between Filipino and Mexican food. I had come across stories about the Manila - Acapulco galleon trade, and I wanted to explore whether that long-forgotten connection could translate into something on the plate. One of the dishes from those early pop-ups was a kind of sea bass kinilaw taco. We cured the fish in coconut vinegar, tequila, and calamansi, then served it on masa and ube tortillas. It was a playful idea, maybe even a little chaotic, but it felt like there was something there. A flavour conversation waiting to happen. Some people thought I was mad. Maybe I was. But I kept chasing the idea. Not the dish itself, but the story behind it.

It sparked something in me. I started chasing culinary connections. Was our adobo some distant cousin of cochinita pibil? Did suman and tamales share a common ancestor wrapped in banana leaves? Could mole have made its way to Mindanao, transformed into something darker, nuttier, Filipino?

I wanted to find something tangible. A shared dish. A shared technique. A line I could draw across the Pacific that told a story of kinship through food.

But the deeper I went, the quieter the trail became. What I found was not a grand culinary exchange. There were no recipe swaps between viceroys and gobernadorcillos. No written record of Filipino mole. No tamales reborn in Visayan kitchens. The flavours I had imagined didn’t appear in the archives. What I found instead was people. Movement. Labour. And empire.

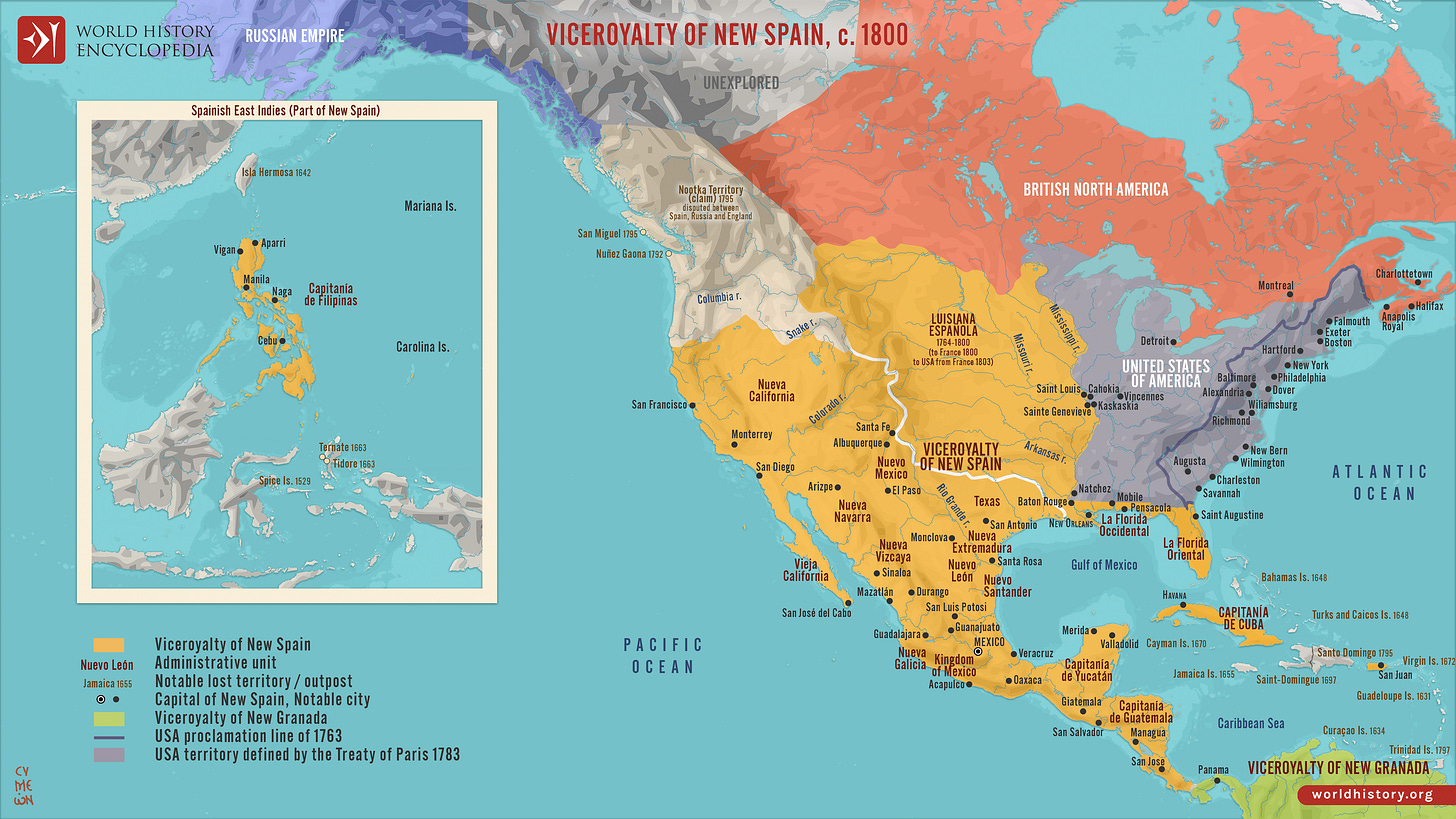

Colonial Mexico Was New Spain

To understand the exchange between the Philippines and Mexico, we first have to reckon with what “Mexico” actually was during the galleon era.

From 1565 to 1815, it wasn’t Mexico. It was New Spain. A colonial viceroyalty ruled from Madrid, where power, wealth, and identity were measured by proximity to Europe. What we now think of as Mexican food, rich with Indigenous knowledge, mestizo identity, and regional pride, did not exist in the form we recognise today. Instead, the food landscape was stratified by race, class, and geography.

In Indigenous communities, maize, cacao, beans, and tamales remained central. But in the urban centres, particularly Mexico City and coastal hubs like Acapulco, elite households followed Spanish tastes. Criollos, American-born Spaniards, and peninsulares, those born in Spain, shaped the upper class. Their kitchens prized wheat over maize, sugar over honey, and European-style sauces over Indigenous preparations. Enslaved and Indigenous cooks prepared these meals but rarely received authorship or credit for their contributions.

As Jeffrey Pilcher writes in ¡Que Vivan Los Tamales!, the colonial elite viewed Indigenous foodways as something to distance themselves from. Maize was considered common. Tamales were seen as rustic. The aspiration was European. Food became a performance of power. Even ingredients like cacao, which held sacred value in Indigenous cultures, were repackaged and sweetened to suit colonial palates.

Sophie Coe’s America’s First Cuisines adds another layer. She points out that while Indigenous food knowledge was complex and widespread, it was rarely the version exported or documented. The culinary authority in New Spain remained with the colonisers, not with the communities who had cultivated those ingredients for centuries.

So if there was any kind of culinary exchange between Manila and Acapulco, it likely did not involve the Indigenous peoples of either land. It passed instead through the hands of Spanish administrators, merchants, clergy, and military officers. The foodways of the Nahua, Mixtec, Zapotec, and other Indigenous peoples were not deemed worthy of international trade, let alone archival record.

This is not to erase those cultures. It is to clarify that the movement of food and flavour across the Pacific was not a conversation between equals. It was trade under empire, shaped by hierarchy, gatekeeping, and extractive intent. If we want to understand what crossed the ocean and what didn’t, we need to begin with who held the power to decide what was written down and what was forgotten.

What the Galleons Carried and What They Didn’t

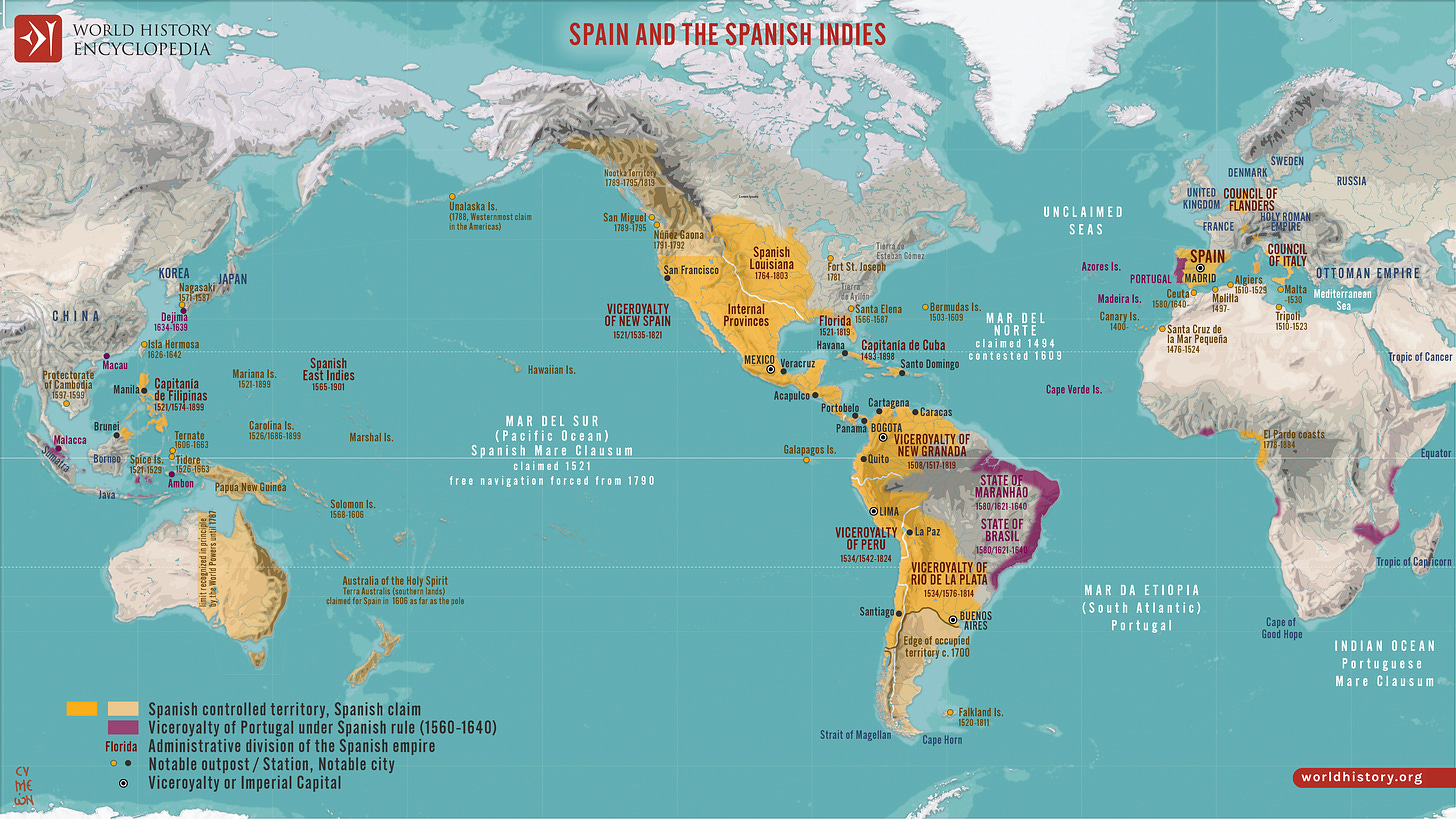

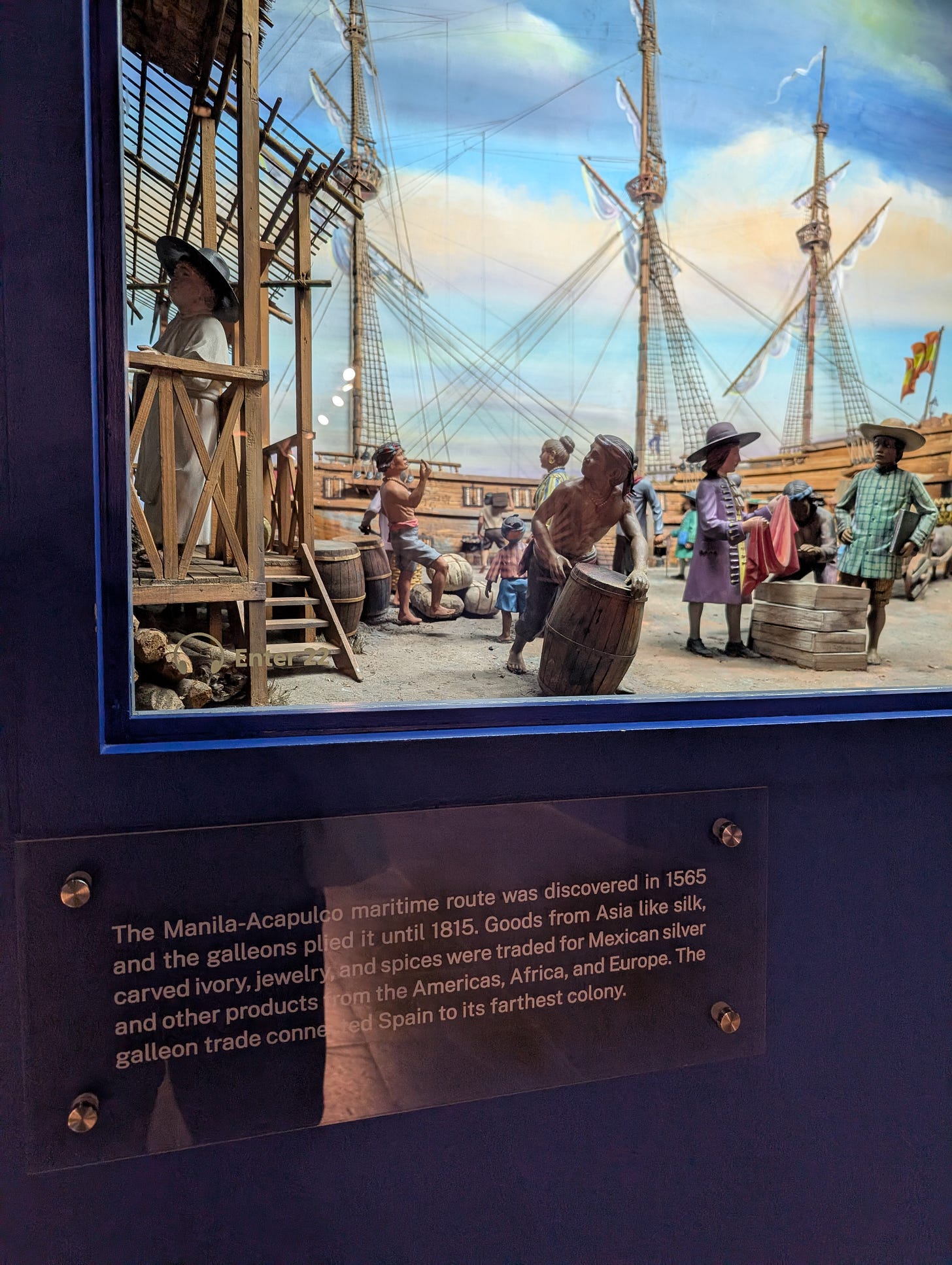

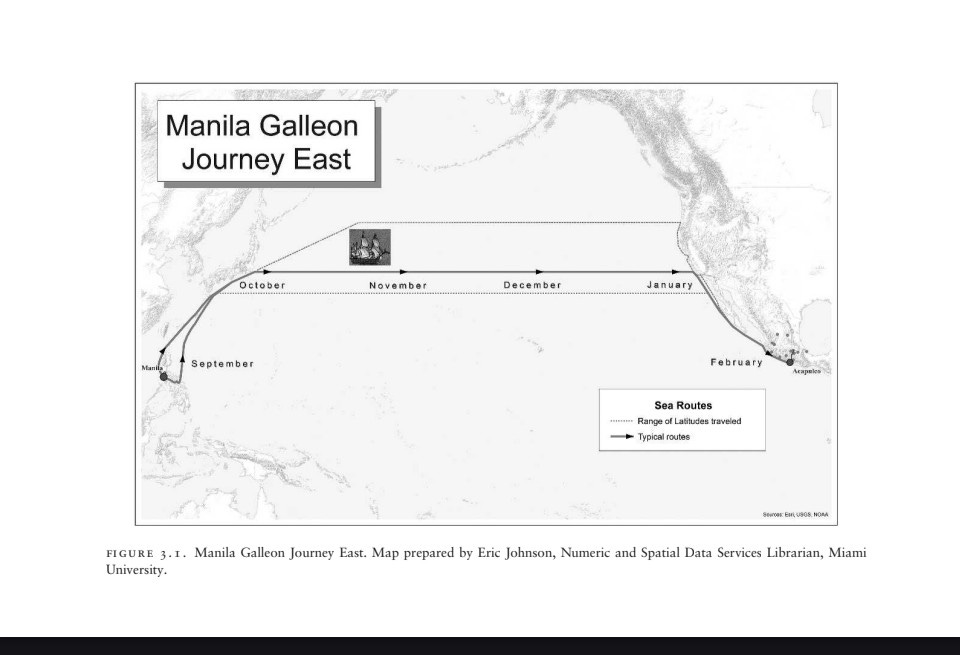

The Manila - Acapulco galleon trade, which lasted from 1565 to 1815, is often romanticised as a grand cultural exchange between Asia and the Americas. But in truth, it was a tightly controlled trade route built for empire. It was designed to move goods, extract wealth, and fortify colonial power. Culture was not the cargo. And yet, it was that same romanticised story that first pulled me in. The idea of shared recipes, intertwined histories, and forgotten flavours felt like a mystery worth chasing. It wasn’t until I looked closer that I began to see what was missing, and why.

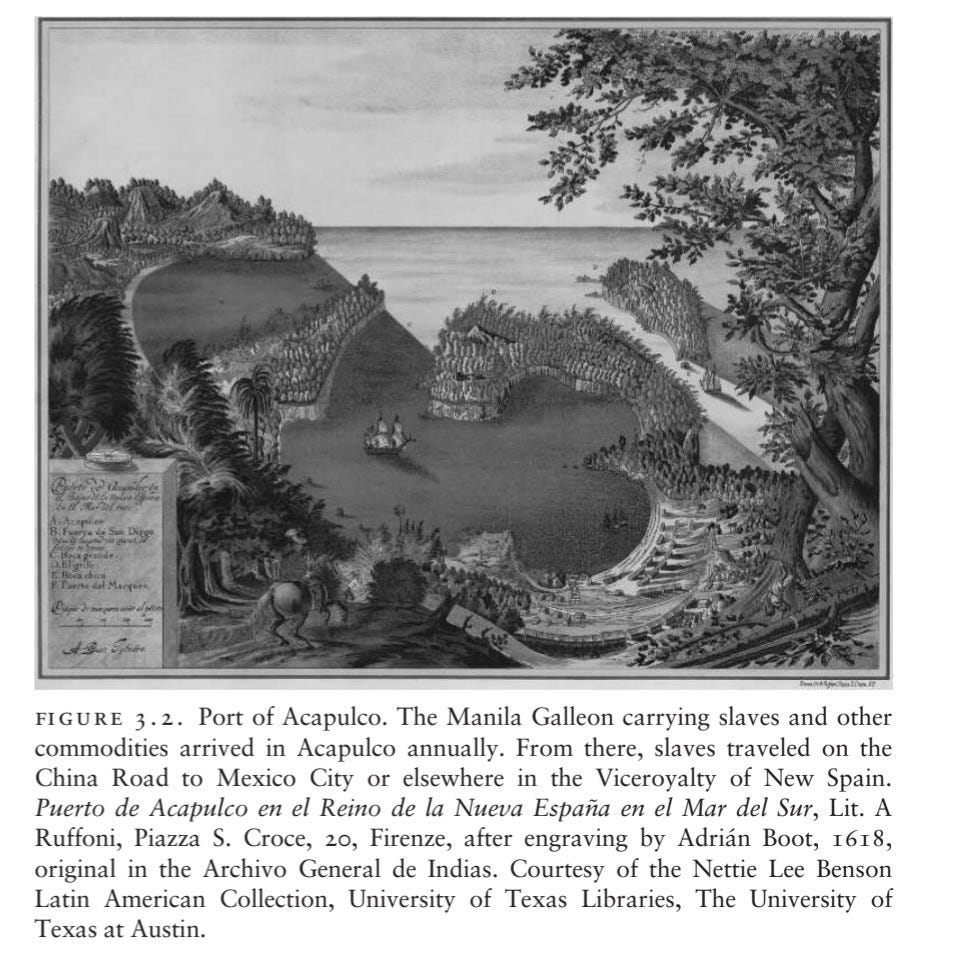

Each year, one or two ships sailed from Manila to Acapulco, packed with commodities sourced from across Asia. The Philippines acted as a logistical hub. It was not the main producer but a trans-shipment point for Chinese, Indian, and Southeast Asian wares. Porcelain, silk, lacquerware, jade, ivory, and spices like clove and nutmeg dominated the cargo. These were luxury items destined for elite consumers in New Spain, and eventually for European markets. Benito Legarda’s After the Galleons describes the trade as rigid, extractive, and focused entirely on high-value goods that could generate profit and uphold colonial hierarchies.

Food was not absent from this exchange, but it was never central. Some plants and ingredients may have crossed the ocean in both directions. Cacao moved east to the Philippines. Crops like coconuts, abaca, sugarcane, or mangoes may have moved west, though documentation is limited. These transfers were rarely strategic. They were incidental. Sailors brought what they missed. Migrants carried seeds and memories. Some things simply grew well in the new climate.

Even these movements are difficult to trace. Shipping manifests from the Archivo General de Indias focused on taxable cargo. Perishable or low-value items, especially those related to daily food use, were rarely recorded. Recipes certainly did not travel in writing. If culinary knowledge moved, it moved through people. Through enslaved workers, cooks, sailors, servants, and soldiers. What travelled was not cuisine but technique. It moved informally, in kitchens, along port towns, or by memory.

This is where the possible Filipino connection to mezcal appears. While there is no definitive archival proof, the consistency of this theory across historical accounts suggests a credible influence that was likely passed through practice rather than formal documentation. Filipino settlers and sailors in coastal New Spain brought with them the knowledge and tools to distill coconut spirits like lambanog. When colonial authorities banned coconut-based alcohol in an effort to protect the Spanish wine trade, Indigenous communities are believed to have adapted those distillation methods to agave. This shift gave rise to mezcal and, eventually, to tequila by the early 17th century.

Edward Slack Jr.’s research into Asian migration to New Spain documents the presence of “chinos,” including Filipinos, in port towns like Acapulco and Veracruz. Many of them were sailors, craftsmen, or enslaved labourers who came with skills. Distillation was one of them. Robert Reed, in Colonial Manila, notes that these types of cross-cultural influences rarely appear in formal records. They are felt, not filed. Contemporary Mexican culinary histories rarely mention these links. That silence may not reflect a lack of exchange, but rather the deeper erasures left behind by colonialism on both sides.

There is no official recognition of a Filipino influence on mezcal. The modern narratives around agave spirits are deeply national, tied to Mexican terroir, Indigenous identity, and cultural sovereignty. But none of that erases the possibility that these techniques arrived informally. Quietly. No manifest. No monument. Just knowledge, passed hand to hand.

The galleons themselves were not cultural vessels. They were commercial ones. On board were Filipino indios, Chinese sangley, Malay sailors, and enslaved Southeast Asians. They left no cookbooks or formal records. But they left behind something else. Instincts. A way of wrapping. A method of steaming. A taste for sourness. Quiet habits that crossed the sea, passed on through practice, not prescription.

If we are looking for culinary exchange between the Philippines and Mexico, we will not find it in official archives. It does not appear in recipes or treaties. It appears in the shadows. In what was borrowed without record. In what was retained through repetition. In the quiet movement of labour and technique.

The Return Journey: Filipinos in New Spain

Most accounts of the Manila galleons focus on what left the Philippines. Silks, spices, porcelain, and lacquerware, all sailing west toward Acapulco. The trade is usually framed as a one-way current of goods enriching New Spain and, by extension, Europe. What often gets left out is the return flow. Not just silver or payment, but people. Among them, Filipinos.

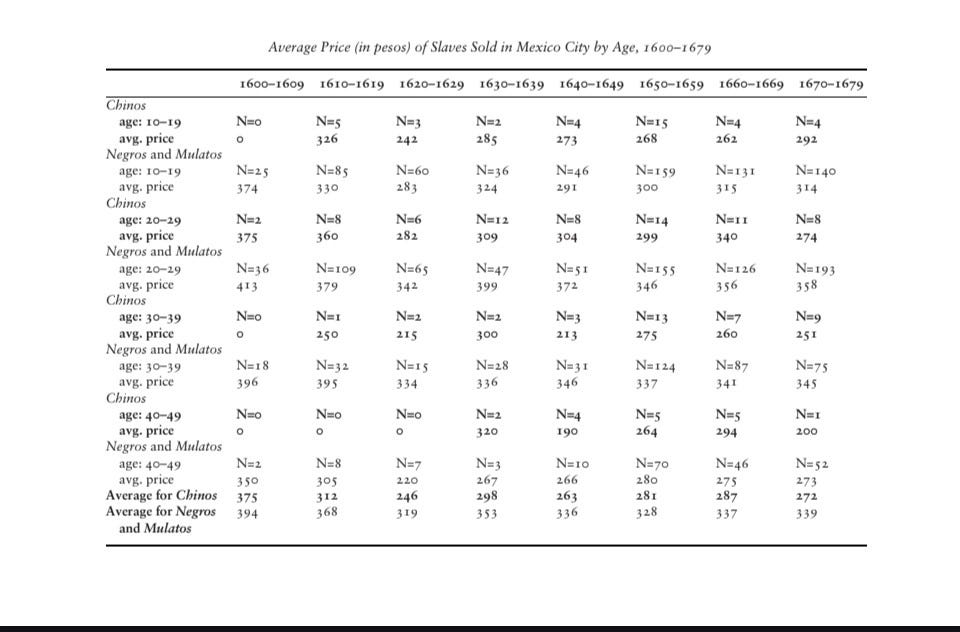

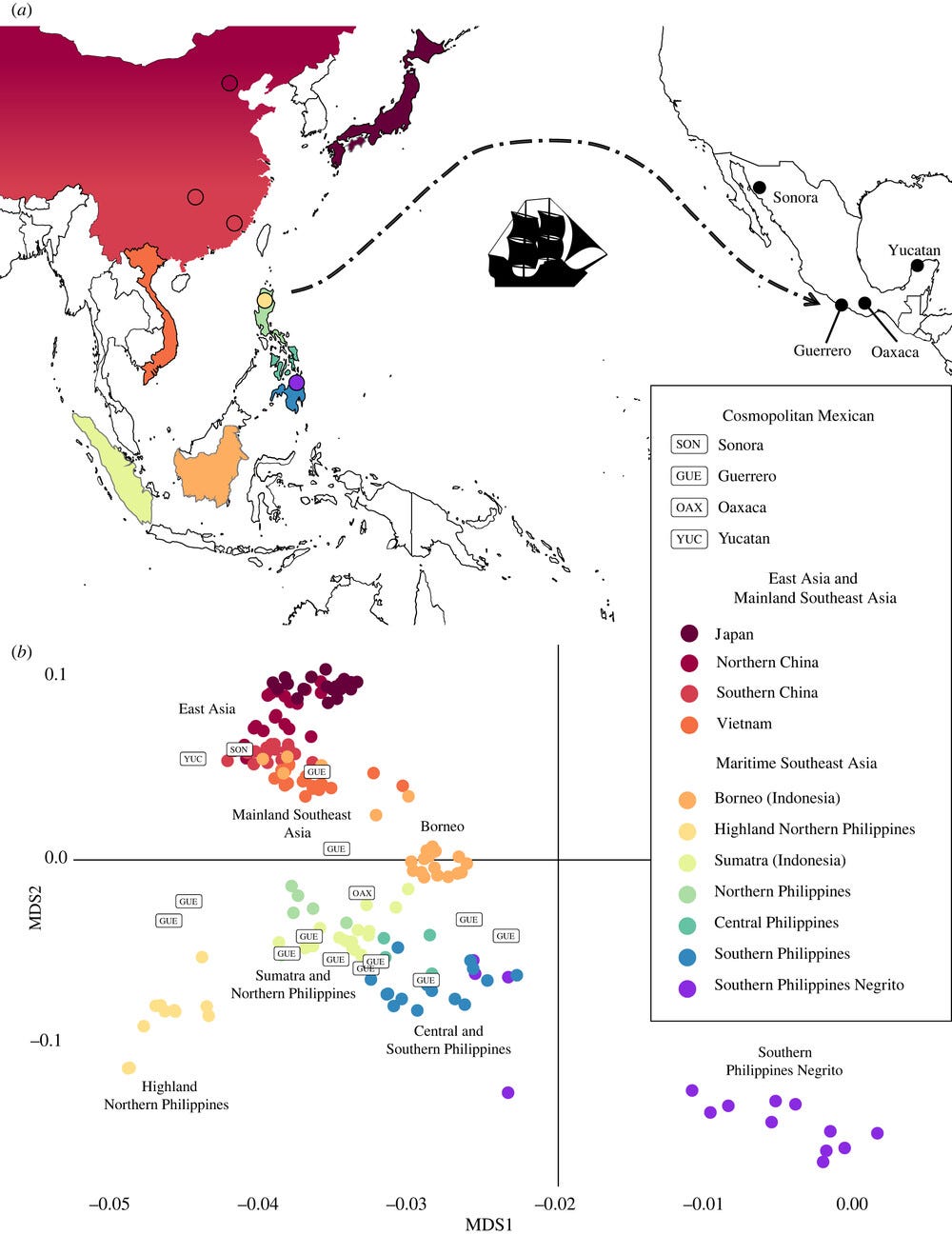

Between the late 1500s and early 1800s, Filipino men were brought to Mexico as sailors, servants, soldiers, and slaves. They were often recorded under the broad term “chinos,” which referred to anyone of Asian origin. Some stayed on after shipwrecks. Others jumped ship. Many were forcibly settled in port towns such as Acapulco, Zihuatanejo, and Colima. Over time, they formed distinct but poorly documented communities.

Historian Edward Slack Jr. has traced how these early migrants contributed to the social fabric of New Spain. His research shows how “Indios Chinos,” a category that included Filipinos, began to embed themselves into daily life. They married into local populations. They worked in agriculture, fishing, domestic service, and artisanal trades. Some became part of local defence militias. Most were absorbed into the lower tiers of colonial society, where names and origins were gradually erased.

As Tatiana Seijas writes, “They were not considered black, nor were they seen as white. The solution was to reclassify many of them as Indians, a group that had specific obligations and privileges in colonial society. Over time, the colonial bureaucracy erased their Asian identities on paper, even while their physical presence remained.”

This wasn’t disappearance. It was deliberate redefinition. A quiet folding in. One that made the Filipino presence in Mexico invisible not through absence, but through paperwork.

Rudy Guevarra Jr., writing about the “Mexipino” connection, describes these migrations as foundational, not incidental. Although they remain largely invisible in national narratives, these early diasporas helped shape everyday life in the coastal towns of western Mexico. Their cultural influence was not spectacular. It was slow, diffused, and undocumented.

When it comes to food, the record is even fainter. There is no surviving Filipino dish that took root in Mexican cuisine. But that does not mean nothing was exchanged. What if the contribution was not a dish, but a method? A way of steaming in banana leaves. The use of vinegar to preserve and tenderise. The instinct to balance sourness with savoury depth. These are not signatures of fusion. They are patterns of adaptation, grounded in necessity and habit.

William Henry Scott’s work on pre-colonial Filipino seafaring documents the construction of balangay boats in the Visayas and Mindanao, made with edge-joined planks lashed without nails. This technique was part of a broader Austronesian maritime tradition. While Scott himself made no claim of trans-Pacific influence, scholars like Edward Slack Jr. and Robert Reed have noted that Filipino presence in parts of Mexico, especially along the Pacific coast, may have left behind more than just surnames. Some small fishing vessels in Guerrero and Colima share construction traits that, while not conclusive, suggest a quiet, undocumented transfer of knowledge. There is no blueprint, but there are material echoes worth considering.

The question is not whether a specific recipe or object made the journey and became something new. It is whether ways of doing, of making, of adjusting to unfamiliar environments, persisted. These forms of influence were unlikely to be named, but they may still be recognisable. A fold in a banana leaf. The choice to use sourness over salt. A boat design that looks strangely familiar.

In the end, what the Philippines gave back may not have been cuisine in the formal sense. It may have been labour. Hands that carried knowledge. Movements that became instinct. Something left behind without ceremony. Not enough to rename the dish, but enough to notice if you know what to taste for.

Echoes Not Recipes

So much of how we define culinary heritage today revolves around traceable, nameable dishes. But many of the techniques that persist, fermenting rice, steaming in leaves, using sourness to preserve, were already part of Indigenous Filipino knowledge systems long before the galleons. What moved across the Pacific may not have been invented at the time, but inherited from much older traditions. Things we can point to and say, “This came from here.” But the echoes between the Philippines and Mexico do not appear that way. There is no mole in Manila. No sinigang in Oaxaca. What remains are fragments. Overlaps in technique. Rhyming tastes rather than mirrored ones.

Take vinegar. In both Filipino and Mexican cooking, vinegar does more than season. It structures. In adobo, in paksiw, in kinilaw, vinegar preserves, cooks, and balances. In Mexico, it appears in escabeche, pickled chillies, and meat marinades. Samin Nosrat described acid as bringing brightness and contrast. In both cuisines, it also brings memory. Whether that similarity came through migration, parallel adaptation, or coincidence is unclear. What matters is the pattern.

There is also the use of sweetness in savoury dishes. Filipino food often softens salt and acidity with sugar. It is common to add a pinch of brown sugar to stews or caramelise aromatics to add depth. In Mexican cooking, the logic is similar. Piloncillo deepens moles. Fruit is added to meat dishes. Tamarind and honey appear in sauces. This shared tolerance for contrast may not have crossed the ocean, but it suggests a similar refusal to flatten flavour. Neither cuisine is built on subtlety. Both are built on layering.

People often point to champorado and champurrado as evidence of shared culinary history. Both are breakfast porridges flavoured with chocolate. Both trace their roots to cacao. But the resemblance fades under scrutiny. Filipino champorado is made with glutinous rice and tablea. It is eaten sweet, often with dried fish. Mexican champurrado is thickened with maize masa and consumed as a hot drink. The shared ingredient does not make them the same. If anything, it reflects the eastward movement of cacao rather than a deliberate exchange of recipes.

Banana leaves offer another point of comparison. Both cultures wrap and steam food inside them. Tamales, suman, pasteles, binalot. Different starches and fillings, but the same instinct. The use of what is abundant. The desire to preserve, transport, and feed many. The logic is practical, not symbolic.

These are not fusion dishes. They are not the result of planned interaction or culinary diplomacy. They are echoes. Habits of survival. Methods of cooking that made sense to people who had little and needed to make it last.

Krishnendu Ray, writing about diasporic food cultures, argues that many cuisines born under colonialism are shaped less by invention and more by adaptation. They reflect constraint, not abundance. They evolve out of preservation, not celebration. This idea fits what we see between the Philippines and Mexico. The similarities are not evidence of culinary hybridity. They are evidence of shared conditions.

Techniques like fermentation, long braising, pickling, or steaming in leaves emerge not because two cultures were in dialogue, but because the conditions they faced demanded similar solutions. No refrigeration. Limited protein. Abundant acidity. Seasonal surplus. The logic is environmental and economic, not diplomatic.

What connects the two cuisines is not a dish. It is a pattern. One built around adaptation, repetition, and endurance.

Imperialism, Not Cuisine, Was the Main Export

After everything that moved between Manila and Acapulco, it becomes difficult to ignore the most consistent force in play. What truly connected the Philippines and Mexico during the galleon era was not cuisine. It was colonialism.

Both territories operated under the same imperial architecture. Both were managed by administrators loyal to Madrid. Both fed their goods, labour, and natural resources into an economic system that benefited Europe at their expense. The galleons were not cultural bridges. They were commercial instruments of extraction.

What we now call Mexican cuisine, rich with Indigenous ingredients, regional variation, and mestizo identity, only took shape after independence. The colonial period in New Spain saw the suppression and marginalisation of Indigenous foodways. Maize, cacao, and chillies were used, but rarely celebrated. Culinary prestige lay with wheat, sugar, and European technique. The idea that Mexican food could be a source of national pride emerged in the nineteenth century, as the post-colonial state began crafting a cohesive identity.

In the Philippines, the process was slower and more fragmented. Our culinary inheritance is still deeply shaped by Spanish and American influence. Doreen Fernandez wrote that “to eat is to remember.” But under empire, memory becomes fractured. The food that persisted did so in spite of colonial rule, not because of it. Dishes like adobo or lechon remain, but so do the hierarchies embedded in how we describe and value them.

Vicente Rafael, in Contracting Colonialism, examines how language, and by extension identity, was shaped through the act of translation. Even our self-understanding was filtered through a coloniser’s vocabulary. The same applies to food. The names we use, the techniques we preserve, and the ingredients we prioritise all reflect centuries of outside rule. They are marked by what was allowed to survive.

This is not to say that cuisine is powerless. But it is not neutral either. The flavours we now identify as Filipino or Mexican have been curated through processes of domination, adaptation, and survival. What appears to be similarity might instead reflect parallel forms of erasure. What tastes like fusion may simply be survival, shaped by absence more than exchange.

If the Philippines and Mexico have a culinary connection, it is not through dishes traded across the sea. It is through the way both cuisines were bent to serve empire, then slowly reclaimed by the people meant to forget them.

What Remains When The Empire Falls

I went looking for mole in Manila.

What I found instead was migration. Memory. And the silence of shared survival.

There were no grand culinary connections between the Philippines and Mexico waiting to be unearthed. No lost dishes. No hidden fusion. What linked us wasn’t a recipe. It was the residue of empire. The aftertaste of labour, trade, and forgetting.

But there’s a kinship in that. Not culinary, but structural. Not built on flavour, but on fracture. A shared history of being ruled, renamed, and reduced. A familiarity in how both of us had to make sense of what was left behind.

Mexico, in many ways, has already done the work of reclamation. Its food is globally recognised. Proudly regional. Complex without apology. It speaks not just to heritage, but to power. That didn’t happen overnight. It took years of revaluation, of putting Indigenous and working-class foodways back at the centre.

I look to that with hope. Not in envy, but in alignment. I want that for Filipino food. For our stories to be told without having to explain ourselves. For our kitchens to feel no pressure to translate. For our cuisine to be recognised not as fusion or trend, but as culture with weight and history behind it.

This is not a search for what should have been. It is a recognition of what was. A way to read between the silences. Not for validation, but for clarity.

We may never be able to point to a single recipe and say, this proves we are connected. But we can look at what persists. At how both cuisines carry the weight of survival. At how taste, even when undocumented, still moves across water.

Sources Consulted

William Henry Scott, Barangay: Sixteenth-Century Philippine Culture and Society

Edward Slack Jr., “The Chinos in New Spain: A Corrective Lens for a Distorted Image,” Journal of World History, 1995

Edward Slack Jr., “Filipinos in Mexico’s Colonial Pacific: Asian Migration and the Manila Galleon Trade,” Journal of Pacific History, 2009

Robert R. Reed, Colonial Manila: The Context of Hispanic Urbanism and Process of Morphogenesis

Jeffrey M. Pilcher, Planet Taco: A Global History of Mexican Food

Sophie D. Coe, America’s First Cuisines

Vicente L. Rafael, Contracting Colonialism: Translation and Christian Conversion in Tagalog Society under Early Spanish Rule

Rudy P. Guevarra Jr., Becoming Mexipino: Multiethnic Identities and Communities in San Diego

Krishnendu Ray, The Ethnic Restaurateur

Daniel T. Reff, “The Spiritual Conquest Reexamined: Baptism and Christian Identity in Colonial Mexico,” Latin American Research Review, 1995

Michael R. M. Jenks, “The Manila Galleons,” Encyclopedia of Maritime and Offshore Engineering, 2017

This was beautifully written and so informative. I devoured it before breakfast. And I will probably want to read it again and again. I imagined it rewritten as a micro history project in the spirit of Carlo Ginzburg's Cheese and worms, but also as a historical novel by Amitav Ghost.

I am hungry for more stories on this, even if imagined ones, not rooted in archival data.

Wow…very informative and well researched. Thanks for this piece.